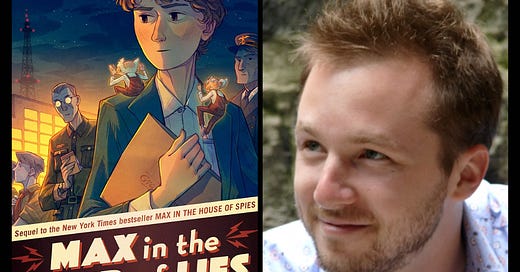

I honestly think that Max in the Land of Lies is one of the most important books of the moment, because it demonstrates how “the Big Lie” works. In a breathless fantasy adventure set during WWII, Adam Gidwitz makes clear how propaganda works and how a population can commit themselves to fake news. It’s not just history, it’s incredibly relevant in our current world, and I am grateful to Adam for helping us understand it.

Max in the Land of Lies is the second part of a duology, begun last year with Max in the House of Spies. I interviewed Adam last July about the first book - LISTEN HERE!

As a reader, I love Adam’s compelling, fun, and profound writing. As a podcaster, I appreciate his fascinating insights, his clear, expressive speaking voice, and his lack of verbal tics (makes for easy editing!). I am positive that you will love this episode as much as I do.

Love, Heidi

NEWS

There’s a new Sydney Taylor Portal on the website of the Association of Jewish Libraries, a hub for information about the life and works of the author of All-of-a-Kind Family.

My “Jewish Joy” series continues on Multicultural Kid Blogs. Here’s my interview with Sephardic authors Sarah Aroeste & Bridget Hodder.

CALL TO ACTION

Adam’s Max in the Land of Lies shows us the dangers of authoritarianism. Protect Democracy has created a toolkit, The Faithful Fight, that helps religious communities defend our neighbors and build a stronger democracy. Check it out HERE.

SHOW NOTES

Tikkun Olam suggestions: EveryLibrary.org and SGCCAmerica.com

"Espionage! Secrets! Suspense!" Holocaust Books with Adam Gidwitz & Steve Sheinkin” on The Book of Life, July 2024

TRANSCRIPT

Note - If you are reading this in your email, you may need to click at the bottom where it says “[Message clipped] View entire message” to read the entire transcript.

Adam Gidwitz 0:00

[COLD OPEN] The prime motivation of just about everybody in the world is to feel emotionally comfortable, satiated, proud of yourself. And we will do or say or believe almost anything to achieve emotional comfort.

Heidi Rabinowitz 0:15

[MUSIC, INTRO] This is The Book of Life, a show about Jewish kidlit, mostly. I'm Heidi Rabinowitz. Last July, Adam Gidwitz was on the podcast talking about his middle grade Holocaust historical fantasy novel, Max in the House of Spies, and he told us it was part of a duology. Well, now the second book is out, and I think it's even more powerful than the first one. Max in the Land of Lies continues Max's page turning, hair raising adventures, and continues the profound exploration of prejudice that we found in Book One. Adam offers the best explanation I've ever encountered for how the Holocaust could happen. The parallels with today's world are frightening and illuminating. To put it simply, this is a book that I think everyone needs to read right now. For show notes, a transcript, and links to more about Adam's work, subscribe to my newsletter at BookOfLifePodcast.substack.com where you'll also get bonus content like Jewish kidlit news and calls to action. And of course, you can visit the full website at BookOfLifePodcast.com. [END MUSIC]

Heidi Rabinowitz 1:32

Adam, welcome back to The Book of Life.

Adam Gidwitz 1:34

Thank you so so much for having me back.

Heidi Rabinowitz 1:37

I had you on the podcast last year in July 2024 to talk about Max in the House of Spies. You were here along with Steve Sheinkin, who wrote the nonfiction book Impossible Escape, about Rudy Vrba's harrowing escape from Auschwitz, and it was a really great interview. I'll link to it in the show notes for anyone who wants to go back and listen to it. And I wouldn't normally have somebody back to talk about the sequel of their book, but I felt that Max in the Land of Lies was a very important book, and I really wanted to draw people's attention to it. Can you recap for us, Max in the House of Spies, and then add a brief description of the sequel, Max in the Land of Lies?

Adam Gidwitz 2:18

Yes, and I would just like to say an enormous thank you for bringing me back and for recognizing the sort of unique nature of this duology. So the first book, Max in the House of Spies, starts in 1938 in Germany. Max is a Jewish boy who becomes a part of the Kindertransport. His parents put him on a train, which takes him to a ferry, which takes him to England, a country he's never been to. He barely speaks any English. And he gets placed with a family who was a real historical family, the Montagus. Jewish family, wealthy Jewish family. The uncle in that family, Ewen Montagu was high up in British intelligence. So Max is a genius, and he wants to try to get back to Nazi Germany, which may sound crazy to most of us, but he is a kid living in a time when the Holocaust has not happened yet, and he has been separated from his parents, and he wants to go back and help them, because he is a genius. He's always been the sort of the macher in the family, the one who can make things happen, make things work. And so using his skill with radios and his natural ability to sort of predict what's going to happen ten minutes before anyone else can see it, he tries to get himself trained as a spy by Ewen Montagu and sent back to Nazi Germany. That's Book One. Book Two takes place immediately after he crash lands in Nazi Germany. So spoiler alert, at the end of that book, he parachutes into Nazi Germany attached to a commando. The commando dies on impact with the ground, and Max ends the first book harnessed to a dead man. And so the second book begins with him getting unharnessed and setting out into Nazi Germany. And he has an official mission that the British have told him that he is to infiltrate the Funkhaus, which was the center of Nazi radio programming and propaganda. But he has a secret mission which he has not told his British spy masters about, which is to try to find his parents. And the one element that I didn't get to mention, briefly, is that he has two immortal creatures who have appeared on his shoulders, Stein and Berg, a kobold and a dybbuk. He's the only one who can see them, and they start out just trying to make his life miserable, heckling him and making wisecracks. But over the course of the two books, their role becomes more integral.

Heidi Rabinowitz 4:38

All right, great. What is so remarkable to me is how you've provided so much context to answer the question of how the Holocaust could happen. Most Holocaust books use this sort of non-answer: that the Nazis just didn't like anyone who was different from them. But that has always seemed like a really weak answer to me. Can you talk about some of the explanations that you've included for how the Holocaust could happen?

Adam Gidwitz 5:04

I'm glad you focused on that, because that was really the prime motivation of this book. And before I answer, I just want to say that I don't take any of these potential partial explanations, you know, flippantly. As a kid, I remember very clearly lying in bed at night and thinking, why? Why would they have hated me so much? And also, how? How could they have brought themselves to do these things, right? It would have taken hundreds of thousands or millions of Germans, in one way or another, to be complicit with the murder of our people and of other peoples as well. And so one of the core motivations of writing the book was to try to understand why. We talked about it a bit last year when I was on the podcast before, about the way the culture of lies has risen in this country, and how that also inspired my investigation of propaganda, and particularly of a people, a populace who has committed themselves to big lies. So you asked, what are some of the reasons I gave. And the way that Max encounters them is he meets a whole bunch of Germans. Some are Nazis, some hate the Nazis, and some are in that big gray area in between. And many of these people give their explanations for why they're doing what they're doing, why they're Nazis, or why they're collaborating with the Nazis, or why they're not standing up to the Nazis. And when you take all of these answers and add them together, you get a complex portrait of why and how they could have done this.

Adam Gidwitz 6:51

One of the most influential sources that I read in all my research was a study done in the 1970s in France, conducted by a survivor of the occupation of France, and he interviewed, I think, hundreds of Nazi collaborators. When he summarized his work of why did these people collaborate, it was millions of different collaborators and millions of different reasons to collaborate. Everyone came to the Nazi cause for their own reason. So some of them are suffering the shocks of hyperinflation and a loss of prestige. They're not wealthy anymore; they used to be. Some, the loss of World War I and a loss of prestige. There's a really interesting dynamic that I explore a little bit where most of the leading SS members were of the generation that was just too young to have fought in World War I. So their fathers, or their big brothers came home from the front, and they felt like they had no path to being heroes the way their big brothers and fathers were, and so World War II and the Nazis was, was that path. When I was reading about them, I kept thinking about that line from Hamilton, "God, I wish there was a war so we could show them we were worth more than anyone bargained for." And what a... that's a terrible thing to wish for, right? So as many reasons to collaborate as there were collaborators, is the paraphrase of that study, and that's sort of kind of where I came down.

Heidi Rabinowitz 8:30

So you mentioned "the big lie," and this is a term that Hitler used in Mein Kampf, and we know that the same kinds of big lies are being told now, with conspiracy theories and fake news being given credence. So I'm really grateful to you for making the big lie concept understandable to young people and to anybody else who reads this book, because everybody should read this book, not just children. So can you go into a little more detail and explain the idea of the big lie?

Adam Gidwitz 8:59

Sure. The Big Lie was a concept that Hitler popularized in Mein Kampf, and he accused the Jews of perpetrating the big lie. Because, as we know about all great liars, they always accuse other people of doing exactly what they are doing. That is their number one tactic. The concept was that if you tell a small lie, people will sniff it out, because every day in people's own lives, they tell little lies all the time, and so they recognize them. But if you have the chutzpah, to use our terminology, to tell a really big lie, no one will believe you even had the gall to say such a thing, and so they won't believe it could possibly be a lie. And furthermore, even if they have some suspicion that it may not be true, if you repeat it often enough, it will make an imprint in their brain for having been heard very often and for being so outrageous, and that imprint will reside long after they even remember specifically what you said. So that's the technique of the big lie. And yes, as you say, it has become, I believe, an explicit, intentional technique in today's world.

Heidi Rabinowitz 10:06

Thank you for that explanation. It's so recognizable right now. In the book (and probably in real life), Goebbels brags that the Nazis were able to take over Germany by telling convincing stories, meaning propaganda. And Max also makes use of the power of storytelling when he takes over a radio broadcast and he shares his own personal story. So can you share your thoughts on the power and significance of storytelling? You're a storyteller too. So can you talk about in your own life or in human history, however you want to frame it, and how does storytelling figure into our current political moment?

Adam Gidwitz 10:46

That's a huge, a huge question, and I'd love to try to tackle it.

Heidi Rabinowitz 10:50

Yeah. Sorry! [LAUGHTER]

Adam Gidwitz 10:50

No, I love it. So I'll start within my own life, and then sort of zoom out a bit. When I was a kid, what I used to like to do at home was I would play with GI Joes action figures, and I would not set them up in big battles like I saw some of my friends doing. One of the GI Joes would usually be the cool kid from school, and the other one would be me. And the cool kid would say something mean or funny to me, or say something similar to what had been said in school, and then I would respond with the great comeback that I had not been able to come up with during school. [LAUGHER] Or sometimes, you know, my GI Joe would beat up his GI Joe, and that was also very satisfying. The other thing I used to like to do is I played basketball on a hoop on my driveway. I was a lucky kid, had a basketball hoop of my own, and it was super cool, because it could go up to regulation ten feet or down to five feet. And so of course, I would put it down to five feet, and I would dunk and shoot three pointers. And the whole time I would talk to myself and tell myself stories about me making the NBA, what team I would be on, winning the championship. So in my life, from very early age, stories were crucial for me, not just to process my life, but also to live out fantasies that helped me feel mastery, helped me feel powerful, helped me feel good about myself. Storytelling is a complex combination of those things. I also started going to therapy at a fairly young age. I think I was 10 when I first started going and again, that's a type of storytelling, talk therapy. I was sitting there telling the story of my life, and in that case, it was nonfiction, at least it was supposed to be, and usually, usually it was nonfiction. And so that was another way of analyzing my life through stories. So for me, stories have been crucial from the beginning. And then, you know, I never thought of myself as a writer, but I became a teacher. And if your listeners are teachers, they know that the first thing you have to do before you can teach the kids anything is get them to shut their mouths for like two minutes. [LAUGHTER] And I was not very good at doing that... unless I told them stories. It turned out that the one thing that I could do to get kids to be quiet was to tell stories. So I told lots of stories, and eventually I started writing those stories down. So stories became both a way to master my life through fantasy, a way to understand my life through therapy and nonfiction, and then a way to succeed in my life professionally.

Adam Gidwitz 13:17

So from my perspective, stories have been really important, and I think ironically, I didn't plan it this way, but those three uses of story are really relevant to how story was used in Nazi Germany and how story is used today. We can tell nonfiction stories to analyze our world and try to understand better what's happening and why it's happening. We also can tell fantasy stories, stories that aren't true, but that are what we want to be true: we will soon be the proud owners of Greenland. I mean, who knows? Maybe that will happen? My guess is it won't. But we can tell these fantasies to make ourselves feel better, or to motivate people to do other things. And that's the third: advance professionally. Political power is achieved in our culture, for better and not for worse, I would say, by the ability to weave a story. Right? In most cultures, in times past, you won by killing enough people, and often you killed enough people by controlling people through story, through propaganda, through myth. But in our day and age, you're not really allowed to kill your political opponents, so you have to tell a better story than the other side tells. Right now, Trump is the most effective storyteller in America. Before him, Obama was the most effective storyteller in America. So for the sake of professional advancement and gaining power, story also plays that role. So it seems like one of the most important things in the world today, and I think it's been that way for a long time, and Nazi Germany was another case where it was at least this important, if not more so.

Heidi Rabinowitz 14:55

Thank you. That was a fascinating answer.

Adam Gidwitz 14:58

I never thought about any of those things. So I'm glad you asked me, because I sort of, we figured out together.

Heidi Rabinowitz 15:02

Yeah, you came up with that on the fly. That's amazing.

Adam Gidwitz 15:05

I mean, a product of, obviously, all the research and writing I've been doing, but yeah.

Heidi Rabinowitz 15:09

In this time of what I consider true peril for the United States, as our current events parallel the goings on in Nazi Germany, the Max books serve as a warning. But beyond the books, do you personally have any particular message for readers or listeners, what to watch out for, what we should be doing? Any thoughts?

Adam Gidwitz 15:33

Yeah, I think it is becoming more and more dangerous every day, the way in which we demonize people that we don't agree with. I recently posted a video on Instagram about the deportations of the PhD students. The most recent one was Ms Öztürk from Tufts, deported, I think, according to the administration itself, because of opinions she expressed in her op-ed piece in the Tufts newspaper, I think it was. If I've got a couple details wrong, I apologize. And a friend of mine, wonderful author, posted something very similar in writing, and on her post, she had two people just really go after her in the comments. And one said, How dare you talk about her and not bring up, what they called, the genocide of Palestinians. If you can't say the word genocide, this poster said, then how dare you even talk about this. And right below that person, another one said she was a Hamas supporting terrorist and needed to be deported, how dare you not recognize that? And I was like, neither of you are listening to what my friend posted, which was merely, we don't deport people because we disagree with them! But what we all need to be doing is practicing resilient listening, listening to people we disagree with and not shouting them down or deporting them because we disagree with them.

Heidi Rabinowitz 17:03

So you just gave a little hint about resilient listening. Can you define it more specifically?

Adam Gidwitz 17:08

It's honestly a term or an idea that I think needs to be worked on more and fleshed out even more. I learned about it on my trip to Israel in May of 2023, a few months before October 7. We visited a wonderful little school called Hand in Hand. It is part of a small network of schools in Israel where Jewish and Arab Israeli kids go to school together. And it is a really, really hard thing to run a school like that, because, as I'm sure all of your listeners know, there is a lot of anger in both communities, and so finding a way to create one community out of these two communities is an amazing effort that they're making. And does it always work? Of course not. And are they often attacked by the outside community? Yes. You know, their library was broken into and anti-Arab hatred was scrawled on one of the walls in the library, and the books were pulled out from the shelves and destroyed. So it's not easy to run a school like that, but one of the core ideas of the school, which came out of some scholarship, but I think what I'm saying is, like too small a batch of scholarship, so there needs to be more about this... is this concept of resilient listening. Which is that you sit there and you hear something that is painful for you to hear, but is true to that other person. They're not just attacking you, they're telling you their truth, and then they sit and listen while you tell them your truth, and you both just sit there in each other's truths. So an example that we were given was of a kid whose grandparents escaped the Holocaust and came to Israel and finally found the first place in the world where they could be safe and feel free. And then another girl talked about that, that same year that your grandparents came, my grandparents lost their house because of what they call the Nakba, the creation of Israel, and it was the greatest catastrophe that ever happened in our lives. And those two things can be true for those two families at the same time, and to be able to sit in that and feel all those feelings is something that is hard for every one of us to do.

Adam Gidwitz 19:21

And to bring it back to motivations of the Nazis and World War II, one of the things that you'll see as you get towards the end of my book is that the prime motivation of just about everybody in the world is to feel comfortable, to feel emotionally good, to feel satiated, to feel proud of yourself, to feel like you're not under attack, but mostly just to feel emotionally comfortable. And we will do or say or believe almost anything to achieve emotional comfort. And what sometimes happens is we sacrifice the truth or the full view of the truth, or an ability to hear someone else, because we're trying to protect our own comfort.

Heidi Rabinowitz 20:15

Well, that is a perfect segue to my next question. In an interview on the blog Imagination Soup, you said that the major question of Max's story is "between what is right and what you love, and how do you choose?" So how do you choose, and what made you think of asking that question in the first place?

Adam Gidwitz 20:36

I mean, that's exactly this question that people are struggling with in the book, and that Max himself will ultimately have to struggle with at the end of Max in the Land of Lies. I think a lot about Melita Maschmann. I think I talked about her a little bit last year, but all of the presentations I've done about Max in the Land of Lies this year, and it's been a lot of them in schools, have focused on this young woman, Melita Maschmann. She was an older teen when Hitler launched World War II, and she joined up, and her job was to ethnically cleanse Poland by getting Polish and Jewish people out of their homes. And she had fallen in love with the Nazi Party for lots of reasons. She was rebelling against her parents, she felt lost, and the Nazi Party gave her direction and a way to feel useful in the world. But she talks about, in her memoir An Account Rendered, that in all the time that she was evicting Jews and Poles from their homes, she never once thought about how they were feeling. And when I talk to middle schoolers about Melita, I ask them, How is that possible? How could she not think about any of these people, the children, the old ladies, the people that she was evicting from their homes and putting on trains to go, she says she doesn't know where. How could she not feel for them at all? And I get a lot of really great answers from these middle schoolers, but one answer I've heard a number of times that I think most resonates with me, is that she had already made all of these choices in her life to bring her to this place, she had committed herself to Nazism, to Hitler. She had now evicted tens, hundreds, thousands of people from their homes. If at some point during that process evicting these people, she suddenly started thinking, This is wrong. What an enormous emotional bomb would have gone off inside of her. She would have had to say, Oh my God, every decision I've made for the last ten years has been terrible, and I'm doing the wrong thing. And furthermore, how do you get out of that situation without endangering your own life? I'm not trying to sympathize with her. What I'm trying to say is that none of us wants to feel the discomfort, the intellectual dislocation of realizing maybe some fast held belief that we have is wrong. And now I don't remember your question, but I do think it's something that we need to do...

Heidi Rabinowitz 23:20

[LAUGHTER] The question was, how do you choose between what is right and what you love?

Adam Gidwitz 23:26

Yeah, so I think most of us cling to what we love and hope that it's also right. And I think it is incumbent upon all of us to do the hard work of understanding how we could have been wrong. I'm trying to do it right now. I'm trying to be open minded to the fact that, you know, there may be things that Trump is doing that are better than what Biden did. Now, there aren't many of them. In fact, most of them are destroying the government as I see it. And well, we can go on a long laundry list, but there may be a thing here or there that actually he was right about. Right? You know, his immigration like, preventing people from coming out north of the border is at least more effective. And probably Biden could have done that and he didn't. Is it the right thing to do? I'm not sure that it is, but he's clearly better at it. So what are the things that I can do to like crack my mind open and feel the extreme discomfort of realizing that the things that I've held dear as truths may be wrong? I think we have to try.

Heidi Rabinowitz 24:32

In that same interview on Imagination Soup, you said it's often easier to get kids to think critically than adults. Why do you think that is?

Adam Gidwitz 24:42

Oh well, they've been doing it for less time. They haven't built lives around things that they tell themselves they believe. You know, it's an incredible moment when you're 13 years old to suddenly say, I think everything my parents think is wrong! And you can do that because the only consequence is some arguments with your parents, which you're probably jonesing for anyway. Whereas when you're 33 if everything you thought was wrong, do you have to change who you're married to or where you live or the job you do? It's just the pressure of preconceived notions, of confirmation bias becomes so much more intense.

Adam Gidwitz 25:28

But even kids struggle with it. So in 2008 Obama was running against McCain, and I was teaching ninth grade, and I asked my students to raise their hand if they knew who they would vote for in the election, if they were allowed to vote. I said, don't tell me who. Just raise your hand if you knew who you would vote for. And then I said, Put your hand down if that person is different from who you think your parents will vote for. And every hand but one stayed up in the air. In other words, everyone would have voted for the same person their parents were voting for. And I said, you know, I was feeling fairly salty that day, I guess. I said, How lucky all of you are that you just happen to have been born in homes where they have the right political opinions, where they know the truth, just like you do. It's hard even, even for a teenager, to break with what the people around them, the people they live with, the people they love, the people they respect, think. And yet, if we're going to be responsible members of this world, then we have an incumbency upon us to at least try.

Heidi Rabinowitz 26:38

In Max in the Land of Lies, the Nazis point out correctly that Britain has a long history of subjugating other peoples, so they saw it as hypocritical that Britain would call Germany out on something they'd done too. Can you talk about that?

Adam Gidwitz 26:54

Yes, I think the Germans were very explicit in a way that, uncomfortably, a lot of people on the left would recognize in this country today, about the colonial past of Britain and also the United States. They thought it was really ironic that the US would try to prevent them from expanding eastward, because they modeled their eastward expansion on American westward expansion, and just as America killed or removed the Native American people from that land as they moved westward. Germany's plan was to remove the Slavs as they moved east. Likewise, they accused Great Britain of being a colonialist power (hard to argue), and they said that Britain's goal was to just make Germany another colony, like some African country or India or something. Now I don't think that's accurate for a few different reasons, one of which being that Great Britain's colonialism was more racist than that, and so they wouldn't have treated white people the way they treated non white people, but it was a really good argument to motivate Germans to fight for their own survival and their own power. They were absolutely calling out hypocrisy on the part of the United States and on the part of Great Britain. But just because you're calling out someone's hypocrisy doesn't mean you yourself are not being hypocritical or, in fact, evil. I think there's a line that the kobold and the dybbuk say Stein and Berg say at one point, just because Tommy punches somebody in the heads, doesn't mean Jerry can kick them between the legs, right? Just because Great Britain has done bad things doesn't mean Germany can do equally bad things. It's, you know, a classic Whataboutism tactic that we hear about these days. You know, a politician will say, Well, you're accusing me of this; What about her emails?

Adam Gidwitz 28:40

You know, Germany were really, really expert communicators and propagandists. One of the characters who most fascinated me in the research on this book was Hans Fischer. He was like the Walter Cronkite of Nazi Germany. If you read his radio broadcasts, some of which have been translated into English, I don't know about you, I found them bewildering to the point where I was like... WAS England the aggressor in this war? Maybe Germany IS just trying to defend itself. And obviously, then you shake your head, you're like, No, no, that's that's very obviously wrong. But they were very good at using, sometimes accurate arguments, accusations of colonialism or hypocrisy on the part of Great Britain in the United States to try to hide the atrocities that the Germans were committing.

Heidi Rabinowitz 29:26

Max is an incredibly competent kid. Hopefully most kids will not be called upon to survive these kinds of situations. But do you believe that he can serve as a role model for actual children? And do kids need their role models to be realistic?

Adam Gidwitz 29:44

Well, kids certainly don't want their role models to be realistic. I mean, not exclusively. I mean, I used to love Wolverine, but I certainly can't be shot with a bullet and then have my skin expel it. So no, we want to... I said "we" as if I'm still a kid! In some ways, I've just told the truth on myself. [LAUGHTER] We often want our heroes to be greater than us, not realistic, but superhuman. That's why I still watch LeBron James, who, at age 40, is doing things that I could never do. So no, I don't think the role models need to be realistic. And no, I don't think Max is. I don't think any kid could do what Max does. But can we aspire to be smarter and more empathic and braver than we are by going on a journey with a kid who is all those things? I certainly hope so. I certainly believe so.

Heidi Rabinowitz 30:35

It's interesting that Stein the dybbuk and Berg the kobold have been around since the beginning of time, and they say they've met God. So in the world of this book, there's no question that God exists. And that's interesting, because the Holocaust destroyed many people's faith in God. So can you talk about that choice in your story?

Adam Gidwitz 30:56

You know, no one has asked me about that in the two years now I've been talking about these books, so Heidi, you have, you have stumped me. I love fiction about God and supernatural beings who may be related to God. I think it is a really interesting place to live imaginatively, spiritually. I believe in God, you know, about 50% of the time. But for the fiction, it made it just, to me, a mythology that was more fun and richer. I mean, Berg and Stein are constantly talking about whether they can accurately remember the instructions God gave them on the sixth day of creation. It's like one of the recurring topics. So that imaginative landscape, to me, is just fun to play in. But you're right about the irony that so many people lost faith in God during that period. I had not thought about that contradiction. I think that's really interesting.

Heidi Rabinowitz 31:56

So Max is a funkmeister. He's an expert on radios. Are you a funkmeister? Do you know a lot about radios, or did you have to study up for Max's sake?

Adam Gidwitz 32:06

I completely studied up. I don't know nothing about that kind of stuff. The technicalities of it are way beyond me. But luckily, I found a wonderful man in England who sells old radio manuals online for like, two quid a piece. And I wrote to him, and was like, Could I get this radio manual and also the brochure? And he was like, Why? And I told him what I was doing. And he was like, okay, that's not the one you want. Let me help you. And he became a pen pal of mine and helped me on some of the technical things that I desperately, desperately needed help on.

Heidi Rabinowitz 32:38

So HE was the funkmeister!

Adam Gidwitz 32:39

He is absolutely a funkmeister!

Heidi Rabinowitz 32:41

Cool. It's tikkun olam time. What action would you like to call listeners to take to help heal the world?

Adam Gidwitz 32:50

I would encourage you to consider two different organizations and supporting them, either through amplifying their messages or through donating if you can. So one is called EveryLibrary. It's an advocacy group for libraries, and we all know that libraries are currently in the fights of their lives with current federal prosecution and state by state persecution. So EveryLibrary is an advocacy group and a lobbying group that desperately needs more attention and more funding. So I really recommend thinking about them. And then I encourage you to go to the website of my political organization. I have a super PAC founded with three other children's book authors, including Gayle Forman, who writes incredible Jewish content. Our group is called SGCC, and if you go to sgccamerica.com there's information about what we do to flip state legislatures so that they support libraries, schools, children's freedom to grow up and all of our freedom to be our best, healthiest selves. So sgccamerica.com if you want to see what we're doing, I invite you to come and learn more.

Heidi Rabinowitz 34:01

And what does SGCC stand for?

Adam Gidwitz 34:03

Well, it originally standed for the Small Group of Committed Citizens from the Margaret Mead quote, "Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has." But then, when we went to register as a Super PAC, we realized that the Margaret Mead estate doesn't like people using her quotes for political purposes. So we adopted the much more anodyne State Government Citizens Campaign, which is intentionally forgettable, but the spirit of Margaret Mead is still, is still in there. So that's sgccamerica.com.

Heidi Rabinowitz 34:35

That's a good origin story for the name.

Adam Gidwitz 34:37

Thank you.

Heidi Rabinowitz 34:38

Is there an interview question you never get asked that you would like to answer?

Adam Gidwitz 34:42

You did ask me what I never get asked! That whole contradiction of God and the...

Heidi Rabinowitz 34:47

But do you have any other answers? And I don't remember it, last time, whether it was you or Steve who said that the question you wanted to be asked is, Why are you so great at writing?

Adam Gidwitz 34:59

[LAUGHTER] Yeah, that's a good one. No, I honestly, I just would like to say, and please don't cut this out, that you do an unbelievable job of preparing your interviews.

Heidi Rabinowitz 35:11

Oh, thank you!

Adam Gidwitz 35:12

You listen to other podcasts, you read the book, you read the aftermatter. You really think hard about what we are trying to do in our books. You know, I tried to write a book, especially with the second one, Max in the Land of Lies, that is not a normal book, and the fact that you are taking it so seriously and bringing it to readers, right after I was on with you a year ago, I can't really tell you how grateful I am. So please don't cut that. Everyone should know what a good interviewer you are.

Heidi Rabinowitz 35:38

Oh, thanks so much! That really means a lot to me.

Adam Gidwitz 35:41

I mean it.

Heidi Rabinowitz 35:42

I really appreciate your comments about the podcast, because this is the podcast's 20th anniversary this year.

Adam Gidwitz 35:51

Oh my goodness, congratulations!

Heidi Rabinowitz 35:53

Thank you. So it's really interesting to hear somebody else's perspective on what the show has meant to them, or what kind of a job I'm doing, because, you know, I, I'm having fun, but I don't often get that kind of critiques or feedback. So thank you so much for sharing those thoughts.

Adam Gidwitz 36:14

How many podcasts have even been around for 20 years? I mean that that word is barely 20 years old, is it?

Heidi Rabinowitz 36:19

It was pretty new at the time, I was an early adopter.

Adam Gidwitz 36:22

Good for you, and yeah, the depth of quality I think we all should crave, I know all your listeners do crave, actual, thoughtful content. I'm really grateful to you for the niche you've carved out for yourself and the way you do it.

Heidi Rabinowitz 36:36

Thank you. I guess 20 years of practice, you know, has worked out for me!

Adam Gidwitz 36:40

Paid off! You've definitely logged your 10,000 hours.

Heidi Rabinowitz 36:44

Yeah. What are you working on next?

Adam Gidwitz 36:49

I have two projects coming up. One is a graphic novel adaptation of my podcast. Grimm Grimmer Grimmest. I think I might have talked to you about that last time. In my podcast Grimm Grimmer Grimmest, I tell Grimm fairy tales live to kids, and they are the weird ones and the unknown ones. So I've taken three of those stories, Hans My Hedgehog, The Iron Shoes and The Wizard King, which it's called The Hamster From the Water originally. So I'd taken those three little known Grimm fairy tales, retold them on the podcast, and now I am re retelling them in graphic novel form, illustrated by the relatively new graphic novel artist Breanna Chambers. And then I have another book that I am hard at work on, and we will see if it ever sees the light of day, which is the story of my great grandfather immigrating to the United States from Lithuania and moving to Mississippi, and his interactions there with the people in Mississippi, the white power brokers and the black sharecroppers alike, which is a tough book to write, but feels very important if I can figure out how to do it well.

Heidi Rabinowitz 37:58

Where can listeners learn more about your work?

Adam Gidwitz 38:00

To learn more about my work, you can go to AdamGidwitz.com but really, the best way to learn more about my work, other than listening to The Book of Life podcast, is to read one of my books and read all the way to the end. I spent a lot of time on the back matter. My wife is a professor of history, and so she does not let me off the hook on any subject, from the bibliography to the citations. So read one of my books. I think that's the best way to get to know what I'm trying to do.

Heidi Rabinowitz 38:26

And you have so many books of so many varieties. I mean, the Max duology is fairly serious, although at the same time it's funny and it's page turning and exciting and...

Adam Gidwitz 38:37

Thank you.

Heidi Rabinowitz 38:37

You know, it's a little of everything, but it has very important messages to share, and then you have other books that are somewhat lighter. The Unicorn Rescue Society, right? Yeah, and I'm sure that you're always working in some kind of important concepts, but some of the books are lighter than others.

Adam Gidwitz 38:55

For sure, some are lighter than others, but we never really shy away from things. I mean, in The Unicorn Rescue Society, I think, in Book Three, which I co wrote with Joseph Bruchac, who's an Abenaki elder from upstate New York, we tackle the Indian schools, you know, the notorious Indian schools. And in the fourth book that I wrote with David Bowles, it's all about the border wall and chupacabras. So it's fun. You know, it's hard for me to stay away from the deeper subjects. So as you say, I deal with it in very different ways, in different books.

Heidi Rabinowitz 39:25

Yeah, well, just to be the Mutual Appreciation Society, I really like that you always manage to combine exciting storytelling and humor with those deeper concepts. You know, a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down, and I think it really works in your storytelling.

Adam Gidwitz 39:43

Thank you. And the way I like to think about it is that my first responsibility as a writer is to write something that a kid wants to read, where they want to read every word on every page, because if they don't do that, then what's the point of anything that I write? But once I have their attention, I might as well do something interesting, challenging, or worthwhile with it.

Heidi Rabinowitz 40:01

Is there anything else that you want to talk about that I haven't thought to ask you?

Adam Gidwitz 40:05

No, but we can go back to how great your podcast is, if you like. [LAUGHTER] Thank you, Heidi, I really appreciate it.

Heidi Rabinowitz 40:12

I mean, I'm all ears to hear how great I am! [LAUGHTER] But I think the listeners would get a little tired of it.

Adam Gidwitz 40:18

They know, they know.

Heidi Rabinowitz 40:20

Adam Gidwitz, thank you so much for speaking with me once again.

Adam Gidwitz 40:24

Thank you so much, Heidi.

Heidi Rabinowitz 40:25

[MUSIC, DEDICATION] In a few weeks, I'll bring you another archival episode, an interview with Adam Gidwitz from 2017 about his award winning middle grade fantasy, The Inquisitors Tale. In the meantime, here's a dedication from Tali Rosenblatt Cohen, who will be my guest in August 2025.

Tali Rosenblatt Cohen 40:48

Hi. My name is Tali Rosenblatt Cohen. I host the podcast The Five Books: Jewish AAuthors on the Books that Shaped Them, and I'll be joining you soon on the Book of Life podcast. I would like to dedicate my episode to my children, who are my favorite readers. [END DEDICATION]

Heidi Rabinowitz 41:07

[MUSIC, OUTRO] Say hi to Heidi at 561-206-2473, or bookoflifepodcast@gmail.com. Subscribe to my newsletter on Substack to join me in growing Jewish joy and shrinking antisemitic hate. Get show notes, transcripts, Jewish kidlit news, and occasional calls to action right in your inbox. Sign up for the newsletter at BookOfLifePodcast.substack.com. You can also find The Book of Life on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. Want to read the books featured on the show? Buy them through bookshop.org/shop/bookoflife to support the podcast and independent bookstores at the same time. You can also help us out by becoming a monthly supporter through Patreon or making a one time donation to our home library, the Feldman Children's Library at Congregation B'nai Israel of Boca Raton, Florida. You'll find links for all of that and more at BookOfLifePodcast.com. Additional support comes from the Association of Jewish Libraries, the leading authority on Judaic librarianship, which also sponsors our sister podcast, Nice Jewish Books, a show about Jewish fiction for adults. Learn more about AJL at JewishLibraries.org. Our background music is provided by the Freilachmakers Klezmer String Band. Thanks for listening and happy reading.

Sheryl Stahl 42:15

[MUSIC, PROMO] In March, Rena Citrin, chair of the Association of Jewish Libraries Fiction Award, told me, not quite in these words, to get my tush in gear and read Joan Leegant's Excellent short story collection, Displaced Persons. I admit it took two months for it to percolate to the top of my To Be Read pile, but I'm thrilled that it finally did. Her stories are full of relatable people, situations, and humor, not to mention delicious sentences. Join me for a conversation with Joan Leegant at JewishLibraries.org/NiceJewishBooks. [END MUSIC]